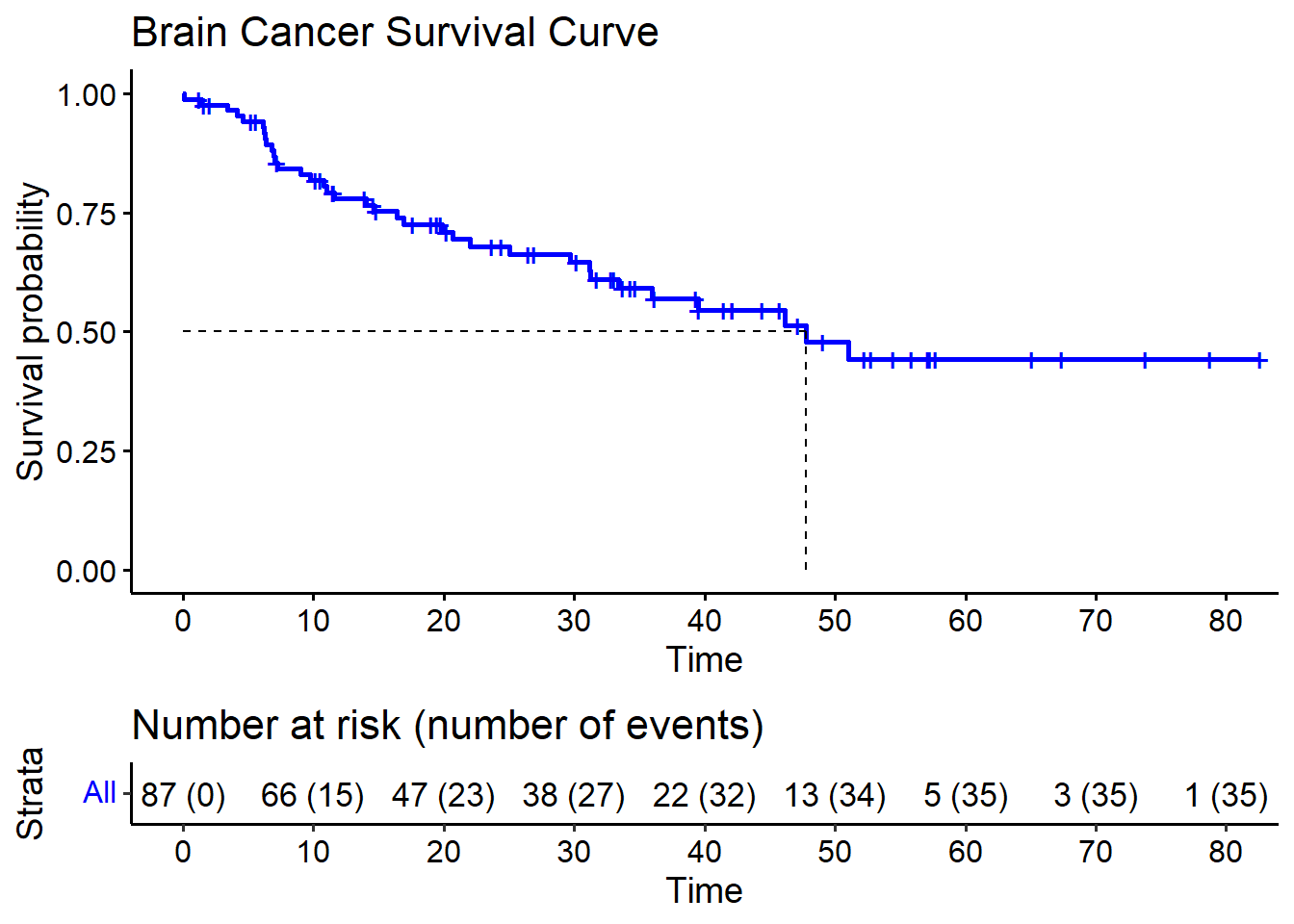

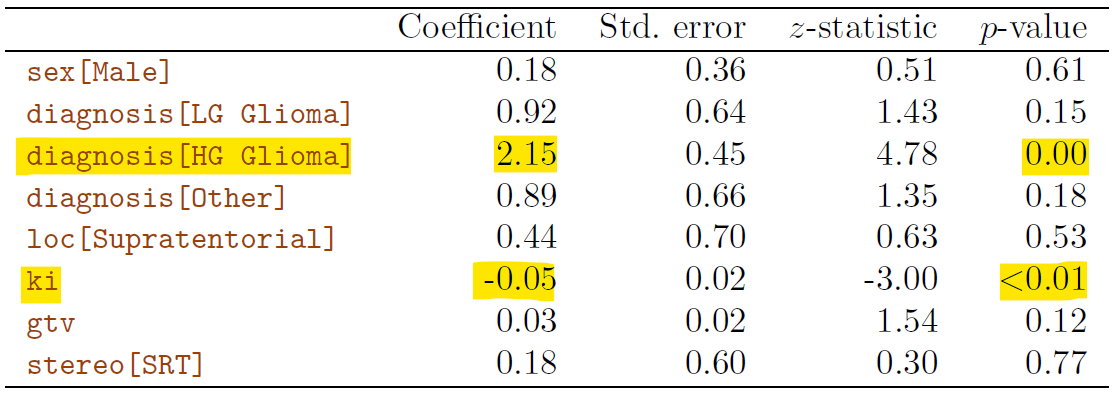

Rows: 87

Columns: 8

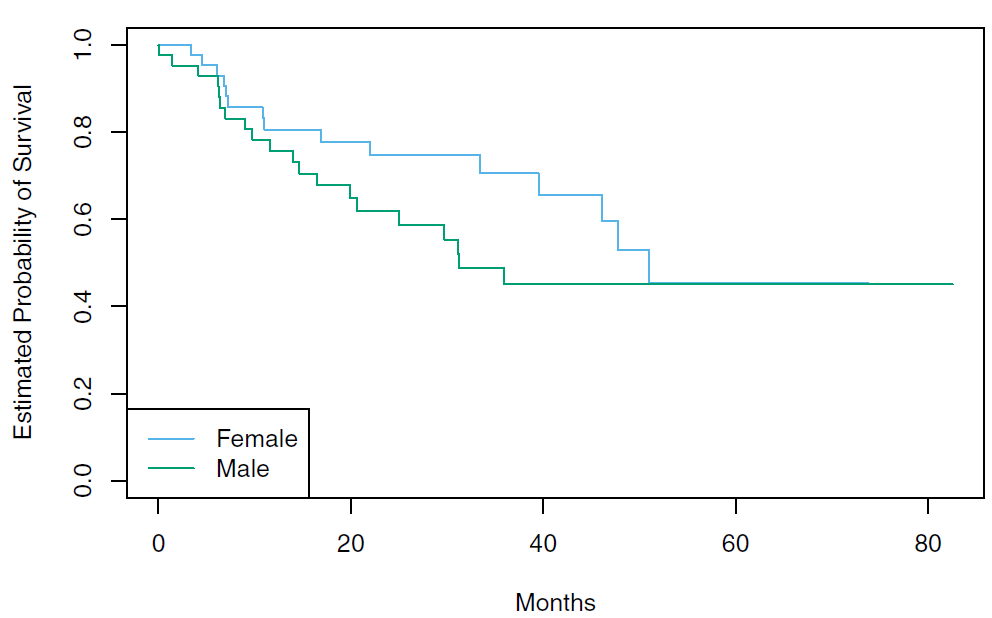

$ sex <fct> Female, Male, Female, Female, Male, Female, Male, Male, Fema…

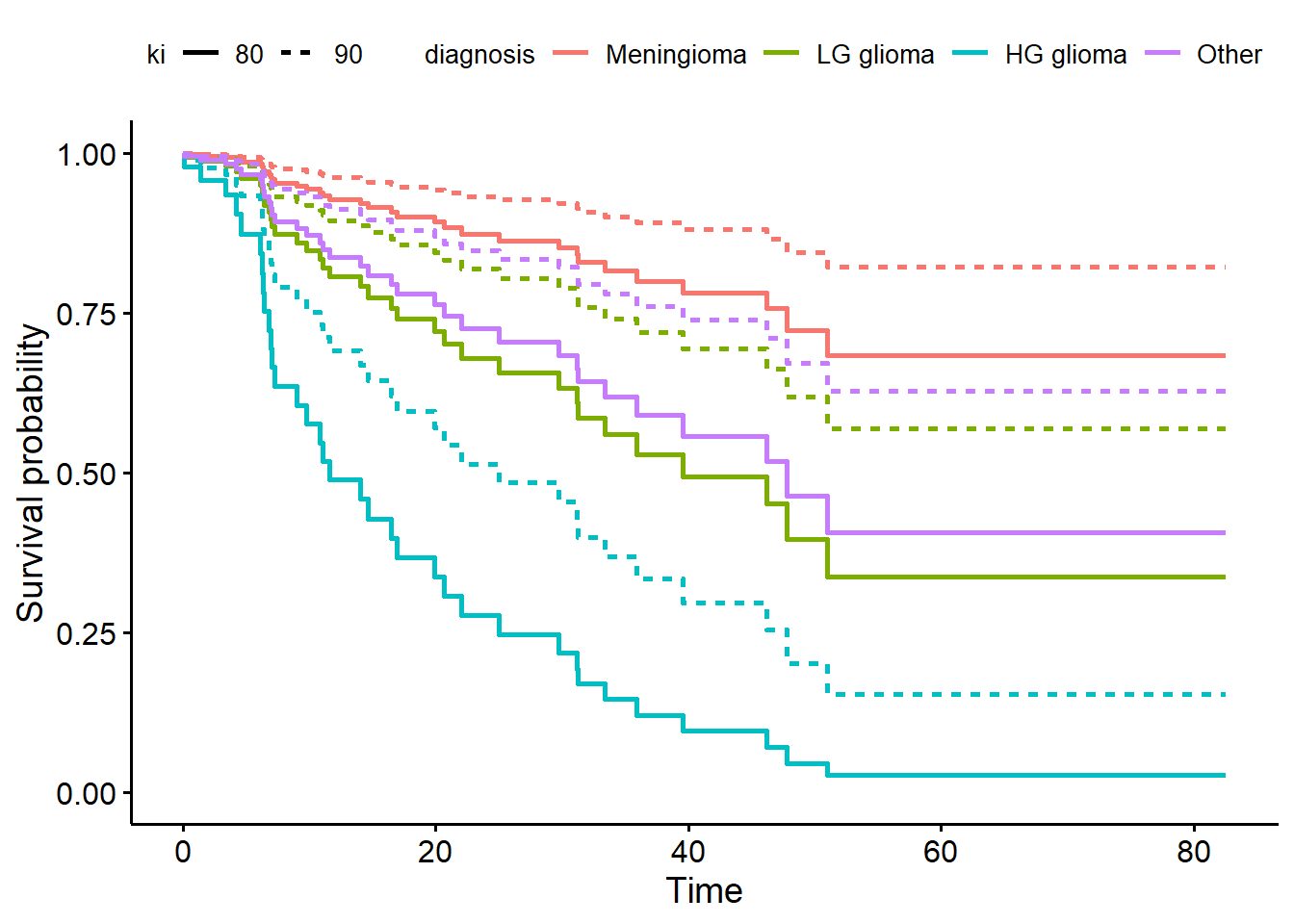

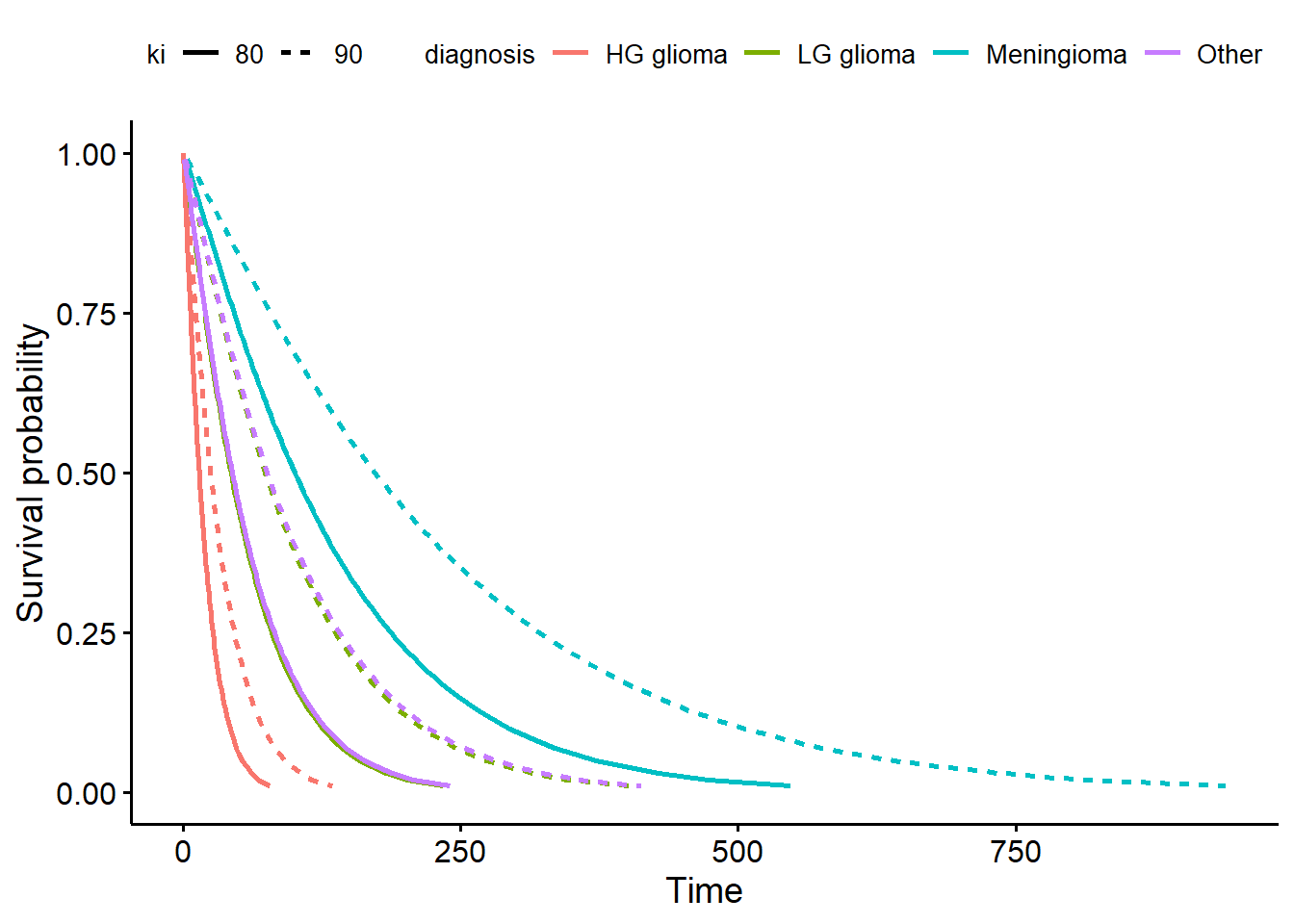

$ diagnosis <fct> Meningioma, HG glioma, Meningioma, LG glioma, HG glioma, Men…

$ loc <fct> Infratentorial, Supratentorial, Infratentorial, Supratentori…

$ ki <int> 90, 90, 70, 80, 90, 80, 80, 80, 70, 100, 80, 90, 90, 60, 70,…

$ gtv <dbl> 6.11, 19.35, 7.95, 7.61, 5.06, 4.82, 3.19, 12.37, 12.16, 2.5…

$ stereo <fct> SRS, SRT, SRS, SRT, SRT, SRS, SRT, SRT, SRT, SRT, SRT, SRS, …

$ status <int> 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, …

$ time <dbl> 57.64, 8.98, 26.46, 47.80, 6.30, 52.75, 55.80, 42.10, 34.66,…