Reducible and irreducible error

The goal when we are analyzing data is to find a function that based on some Predictors and some random noise could explain the Response variable.

\[

Y = f(X) + \epsilon

\]

\(\epsilon\) represent the random error and correspond to the irreducible error as it cannot be predicted using the Predictors in regression models. It would have a mean of 0 unless are missing some relevant Predictors.

In classification models, the irreducible error is represented by the Bayes Error Rate.

\[

1 - E\left(

\underset{j}{max}Pr(Y = j|X)

\right)

\]

An error is reducible if we can improve the accuracy of \(\hat{f}\) by using a most appropriate statistical learning technique to estimate \(f\).

The challenge to achieve that goal it’s that we don’t at the beginning how much of the error correspond to each type.

\[

\begin{split}

E(Y-\hat{Y})^2 & = E[f(X) + \epsilon - \hat{f}(X)]^2 \\

& = \underbrace{[f(X)- \hat{f}(X)]^2}_\text{Reducible} +

\underbrace{Var(\epsilon)}_\text{Irredicible}

\end{split}

\]

The reducible error can be also spitted in two parts:

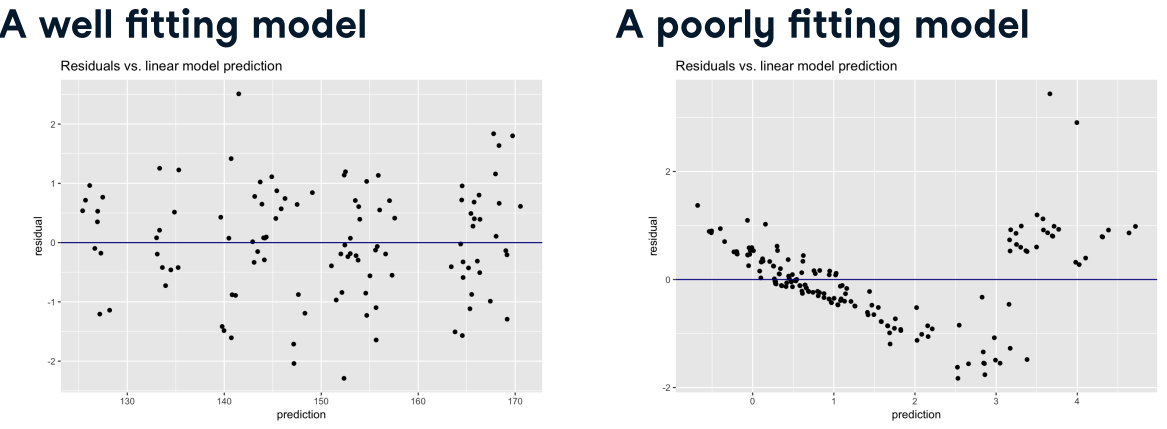

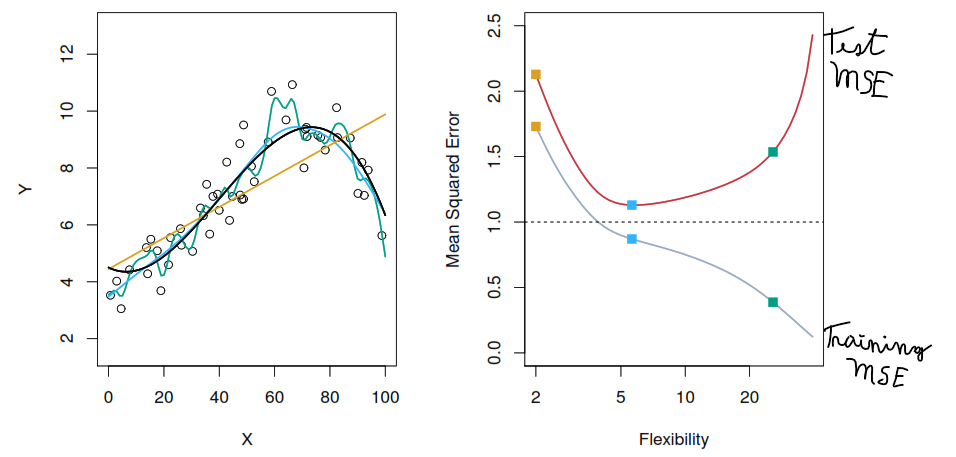

Variance refers to the amount by which \(\hat{f}\) would change if we estimate it using a different training data set. If a method has high variance then small changes in the training data can result in large changes of \(\hat{f}\).

Squared bias refers to the error that is introduced by approximating a real-life problem, which may be extremely complicated, by a much simpler model as for example a linear model.Bias is the difference between the expected (or average) prediction of our model and the correct value which we are trying to predict.

\[

E(y_{0} - \hat{f}(x_{0}))^2 =

Var(\hat{f}(x_{0})) +

[Bias(\hat{f}(x_{0}))]^2 +

Var(\epsilon)

\]

Our challenge lies in finding a method for which both the variance and the squared bias are low.

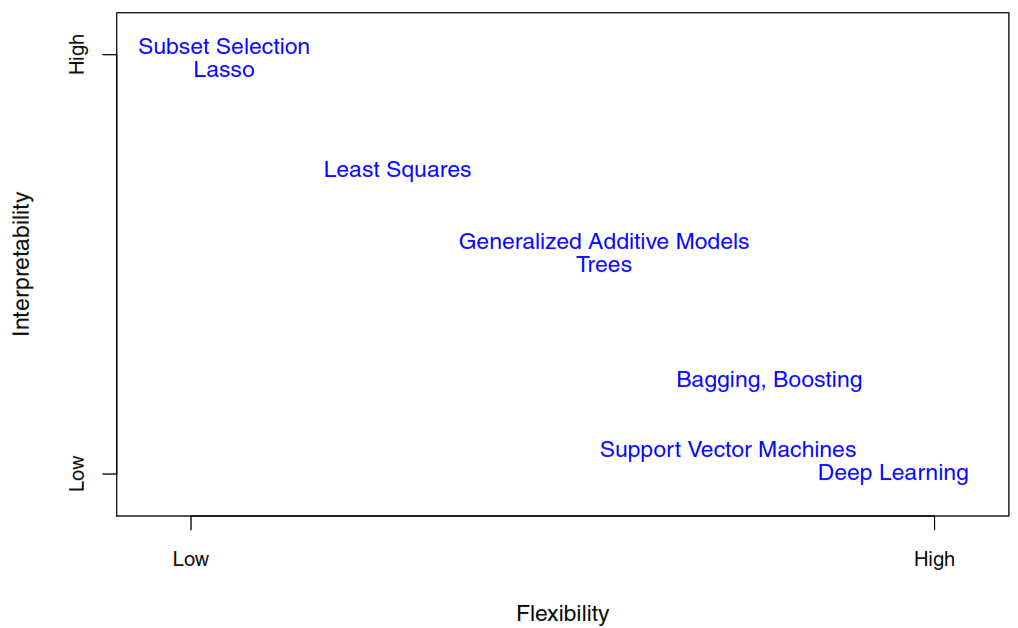

Types of models

-

Parametric methods

- Make an assumption about the functional form. For example, assuming linearity.

- Estimate a small number parameters based on training data.

- Are easy to interpret.

- Tend to outperform non-parametric approaches when there is a small number of observations per predictor.

-

Non-parametric methods

- Don’t make an assumption about the functional form, to accurately fit a wider range of possible shapes for \(f\).

- Need a large number of observations in order to obtain an accurate estimate for \(f\).

- The data analyst must select a level of smoothness (degrees of freedom).